Methodology Overview

This project aimed to evaluate Roman imperial coins authorized by Diocletian and Maximian as Augusti during 284-305 that used deities to support their presentation of Diocletian. Identifying the deity on a coin then permitted an examination of the location of the coin’s mint. Taking these two pieces of information together helped to understand how the co-emperors chose to portray Diocletian in particular locations of the empire. Dating the coin’s production allowed an analysis of gods on coins over a discrete period, which in turn helped to determine changes to deities over time. Furthermore, division of the mints between the Augusti allowed me to compare and contrast portrayals of Diocletian on coins in the easter half of the empire with those of Maximian in the west. Online Coins of the Roman Empire (OCRE) tremendously served as the primary database for this study. However, OCRE was limited by its inability to provide tools necessary for this particular analysis. Therefore, Palladio, a digital tool created by Stanford University, provided mapping, networking, timelines, and filters that proved crucial in evaluating the association of these deities with Diocletian. The mapping and networking tools of Palladio allowed me to visualize the mints that produced coins featuring specific gods, to determine their relationships to one another. Using Palladio raised the question of why these gods would be in those particular parts of the empire. Palladio’s timeline tool identified when certain deities were used, raising the question of why one of the Augusti implemented a particular deity during a particular period. Traditionally, Diocletian has been associated with Jupiter, but analyzing coins through Palladio demonstrated a more complicated relationship with his gods.

Research Question

The project’s aim of evaluating the Roman imperial coins authorized by Diocletian and Maximian as Augusti during 284-305 that used deities to support their presentation of Diocletian remained static from the beginning through its conclusion. An important reason for the research question’s stability is OCRE’s deliverance of a large enough sample of data to satisfy the scope of the analysis. The research question offered the opportunity to go further in depth with its analysis. Due to time constraints, the analysis had to remain on the surface level of the research question. The project could not evaluate coins beyond the data provided by the functions and tools of Palladio. Ideally, a proper scholarly analysis seeking an answer to the research question would require more in-depth research of the scholarship pertaining to ancient numismatics of this period in late antiquity.

Material and Data

This project’s research would have been more difficult if not for the availability of the necessary source material and data from Online Coins of the Roman Empire (OCRE).[1] OCRE provides the most extensive digital collection of Roman imperial coins. Through OCRE’s ‘browse’ feature of more than 40,000 coins, a user can refine the results of coins through ten categories: authority, deity, denomination, issuer, manufacture, material, mint, object type, portrait, region. After refining the search results, a user can download a handy Comma-Separated Values (CSV) file of the resulting data. The CSV file proved crucial in saving significantly valuable time. To generate the CSV file, I only refined two of the available ten categories. The two categories, ‘authority’ and ‘portrait’ were both refined to ‘Diocletian’ for the first data set, returning 156 results. To obtain the second dataset, ‘authority’ was refined to Maximian, and ‘portrait’ was refined to ‘Diocletian,’ returning 864 results. The available data through OCRE raises inevitable questions about the number of coins authorized by each emperor. Maximian being the Augustus of the western half of the Roman empire, likely minted more coins than Diocletian in the east on account of a larger population in the west. Further study would need to be conducted to determine if the disproportionate amount of coins authorized between each emperor skews the data to present a result that is not necessarily accurate.

Data Preparation

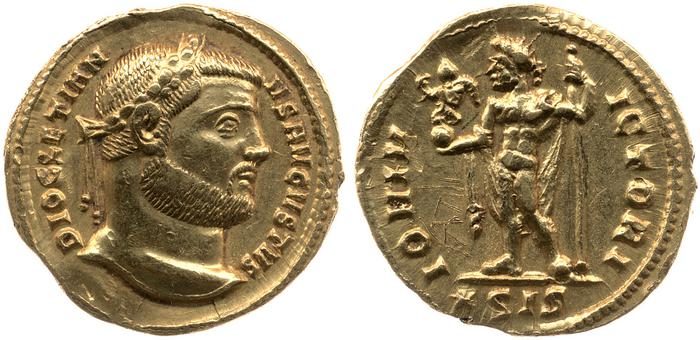

The initial two datasets combined to form 1,020 coins. However, only 711 of these 1,020 coins fit the criteria of including a Diocletian’s portrait and a deity on the coin. Maximian authorized the minting of 619 of the 711 coins, while Diocletian only authorized 92 of the coins. Preparing the data to achieve the 711 coins involved manually editing the data provided by each CSV file. The two CSV files were converted to individual spreadsheets. From there, I examined the ‘reverse type’ of each coin provided by OCRE. The ‘reverse type’ describes the coin’s reverse where deities appear in contrast to Diocletian’s portrait on the coin’s obverse. The coins where OCRE did not provide a deity in its ‘deity’ category but did provide a deity in the ‘reverse type’ received a deity based on the description in the reverse type. Certain coins included more than one deity, but the data provided by OCRE provided only one deity, so the additional deities needed to be added to the spreadsheet. A fraction of the coin listings on OCRE provided images for the coins. Coins that had images received a brief examination to confirm the deity on the coin, and to input the image URL into the spreadsheet for a further purpose with Palladio. After completing the manual affirmation of the data in the spreadsheet, 309 of the original 1,020 coins did not meet the necessary criteria of having a portrait of Diocletian and a deity on the coin, so those 309 coins were excluded from the final dataset. Other elements of data needed to be refined or added to the spreadsheets. Firstly, Palladio may not play as well with date ranges as anticipated. Therefore, any coins featuring date ranges given by OCRE (284-294, 296-298, 300-304, etc.) conservatively received the final year of the date range. Secondly, each coin required geographic coordinates to function with Palladio’s mapping feature, so coordinates for the ancient mints provided by OCRE came from the mints’ pages found on Nomisma.[2] The two datasets were combined to make a single master spreadsheet for the next step.

Palladio

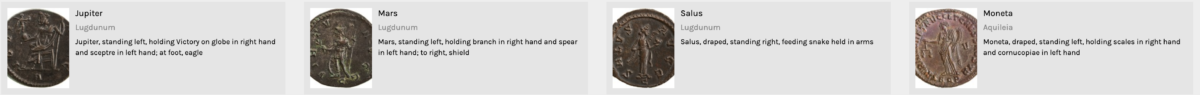

Palladio produced by the Humanities + Design Research Lab at Stanford University served as the digital tool for this project’s analysis. Having presented on Palladio, I recognized its utility and believed it to be potentially a potent tool for the analysis required by this project. Palladio allows data to be presented on a map, in a graph, a table, and a gallery. Additionally, Palladio also has facet, timeline, and timespan filtering. All features of Palladio worked well for this project other than the unused timespan filter. Initially, I anticipated the mapping feature to be Palladio’s most useful tool for this project. However, the map did not connect data points as I had expected it to do so with the dataset. The map did work well to show the location of mints and compare the volume of coins minted at each location. The original expectations for the mapping tool were available in the graph tool that presented networking capabilities. The graph tool visually connected each deity to the shared mints allowing a user to recognize which coins shared the same mints. Additionally, the graph feature provides size nodes based on the number of coins featuring that deity, allowing a user to compare and contrast how numerous that particular god was at a specific mint. The table feature proved to be very useful. It allows data to be sorted by various dimensions. As an example, starting with a row dimension of ‘deity’ 29 rows with a corresponding deity appear. From there, a user may select different dimensions adding nuance to each deity. For the analysis, the most useful dimensions applied to each deity were ‘region,’ ‘mint,’ and ‘year’ to answer the research question. The gallery feature helped in some ways. The most important aspect of the gallery feature is its ability to load images. Less than half of the coins have an image or a functioning image URL, so the gallery does not work well for all coins. Clicking on a coin does link to the coin’s page on OCRE. The most crucial feature of Palladio for this project might be its facet filter. The facet filter allows data to be sorted in different manners interreacting with each Palladio tool. A user can select dimensions similarly to how dimensions are selected in the table tool. Selecting a particular element of the data in the facet filter interacts with corresponding data in the chosen tool. The facet filter appears to have provided the most useful data for the analysis of this project’s research question. Lastly, I anticipated the timeline filter to be a fundamental feature of Palladio for this project. However, the limitations of the data caused the timeline not to be as useful as initially anticipated. For the data with definitive dates, the timeline filter was of great importance.

Data Sharing

I decided to share the data for this project on a website to make it as easily accessible to a potential user. It would be wrong of me to keep research to myself that may benefit another user, so I have chosen to include a JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) file link on the site. An interested user of the data will be able to access the JSON file through the link to its repository on GitHub. Hopefully, in the near future, I will be able to include a step-by-step guide on using the JSON file with Palladio. Palladio has a sizeable learning curve depending on a user’s situation, so it is important to provide instructions on how to use the data to achieve the most useful results for the user.

[1] American Numismatics Society, Online Coins of the Roman Empire, http://numismatics.org/ocre/.

[2] Nomisma.org, http://nomisma.org.