The Project

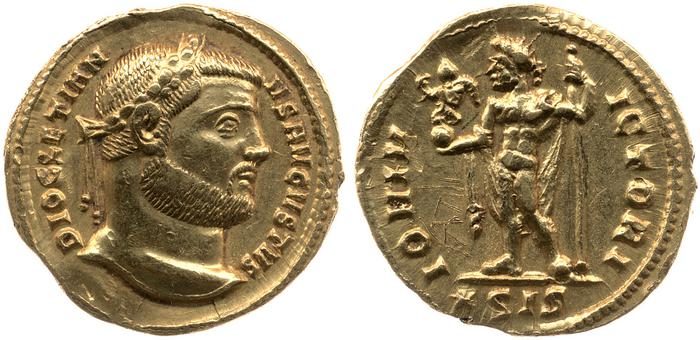

The project aims to evaluate how the Roman imperial coins authorized by Diocletian and Maximian as Augusti during 284-305 used images of deities to support their presentation of Diocletian. Identifying the deity on a coin then permits an examination of the location of the coin’s mint. Taking these two pieces of information together helps us to understand how the co-emperors chose to portray Diocletian in particular locations of the empire. Dating the coin’s production allows an analysis of gods on coins over a discrete period, which in turn helps us to determine changes to deities over time. Furthermore, division of the mints between the Augusti allows us to compare and contrast portrayals of Diocletian on coins in the eastern half of the empire with those of Maximian in the west. Online Coins of the Roman Empire (OCRE) tremendously serves as the primary database for this study. However, OCRE is limited by its inability to provide tools necessary for this particular analysis. Palladio is a digital tool created by Stanford University that provides mapping, networking, and timelines that prove crucial in evaluating the association of these deities with Diocletian. The mapping and networking tools of Palladio allow one to visualize the mints that produced coins featuring specific gods, to determine whether these deities were featured on coins in other areas of the empire, and to try to understand their relationships to one another. Using Palladio has raised the question of why these gods would be in those particular parts of the empire, and its timeline tool, which identifies when certain deities were used, raises the question of why one of the Augusti implemented a particular deity during a particular period. Traditionally, Diocletian has been associated with Jupiter, but analyzing coins through Palladio demonstrates a more complicated relationship with his gods.

Diocletian

Diocletian came into power through unusual circumstances in the third century. The blurry pre-imperial life but the humble social origin of Diocletian draws attention to an emperor different from his predecessors. Frustratingly, Diocletian seems to be an understudied Roman emperor relative to his reign’s length and unique elements. Coming from a new imperial background makes Diocletian all the more attractive in understanding how he used imperial power and how the people of Rome received him. Stephen Williams introduced Diocletian as the restorer of the Roman empire. However, Diocletian restored stability to the empire. He did not restore Rome “as a dignified civic forum but rather as a great fortress.”[1] Diocletian served as a soldier and ruled with a militaristic mind focused on ensuring the strength of the empire. Little information is known about the career of Diocletian before assuming imperial power. At the time of the emperor Numerian’s death, Diocletian commanded the emperor’s bodyguard.[2] At the same time, Numerian’s brother Carinus reigned alongside him after the death of their father, Carus, in 283. In 283, Diocletian received the consulship, and Numerian died soon afterward. Soldiers loyal to Numerian chose and supported Diocletian as the new emperor.[3] Carinus marched to defeat Diocletian, but one of Carinus’ men killed him, leaving Diocletian as sole Augustus in 285.[4]

The new emperor broke the dynastic lines prevalent in the succession of previous emperors. Diocletian inherited an unstable empire as a military man, who also possessed no son of his own to inherit the throne. Alone in his power with a massive Mediterranean empire, Diocletian opted to create a dyarchy. The formation of two rulers began when Diocletian appointed Maximian as Caesar in 285, later elevating him to Augustus in 286. Diocletian based himself in the East at both Sirmium and Nicomedia, while Maximian resided in the West at Trier.[5] The political uniqueness of Diocletian’s rule showed itself demonstrably when Diocletian created what is known as the “First Tetrarchy,” rule by four men beginning in 293 and continuing shortly after the reign of Diocletian. The two additions came in the form of Caesares, with Constantius serving as Caesar under Maximian in the West, and Galerius directed by Diocletian in the East.[6] Diocletian’s reign ended with an unprecedented event as Diocletian and Maximian abdicated their positions as Augusti in 305, allowing the Caesares, Constantius and Galerius, to become Augusti.[7]

[1] Stephen Williams, Diocletian and the Roman Recovery (New York: Methuen, 1985), 12.

[2] David Potter, The Roman Empire at Bay: AD 180-395, 2nd edition (New York: Routledge, 2014), 276.

[3] Roger Rees, Diocletian and the Tetrarchy (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2004), 5.

[4] Potter, The Roman Empire at Bay, 276.

[5] Rees, Diocletian and the Tetrarchy, 6.

[6] Timothy D. Barnes, The New Empire of Diocletian and Constantine (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1982), 4.

[7] Rees, Diocletian and the Tetrarchy, 8.

Christopher Thoms-Bauer, Rutgers University